Blog Post Heading

Blog Post Content

By Heather Morton

Senior Editor, MindEdge Learning

Angela Duckworth gained fame as the social-science researcher who brought the importance of “grit” to national attention.

I think her recent work on self-control is even more revolutionary, pointing out the ways we can intervene early to avoid temptation rather than have to struggle against it later—so that maybe we don’t need so much grit to get by, after all.

The ability to avoid temptation is particularly important in remote schooling situations, which require a lot of what we normally call “self-control” from students: staying focused on school content during video chats, getting work done on time, and avoiding the kinds of behavior (such as spending hours on social media sites) that might lead to depression and anxiety.

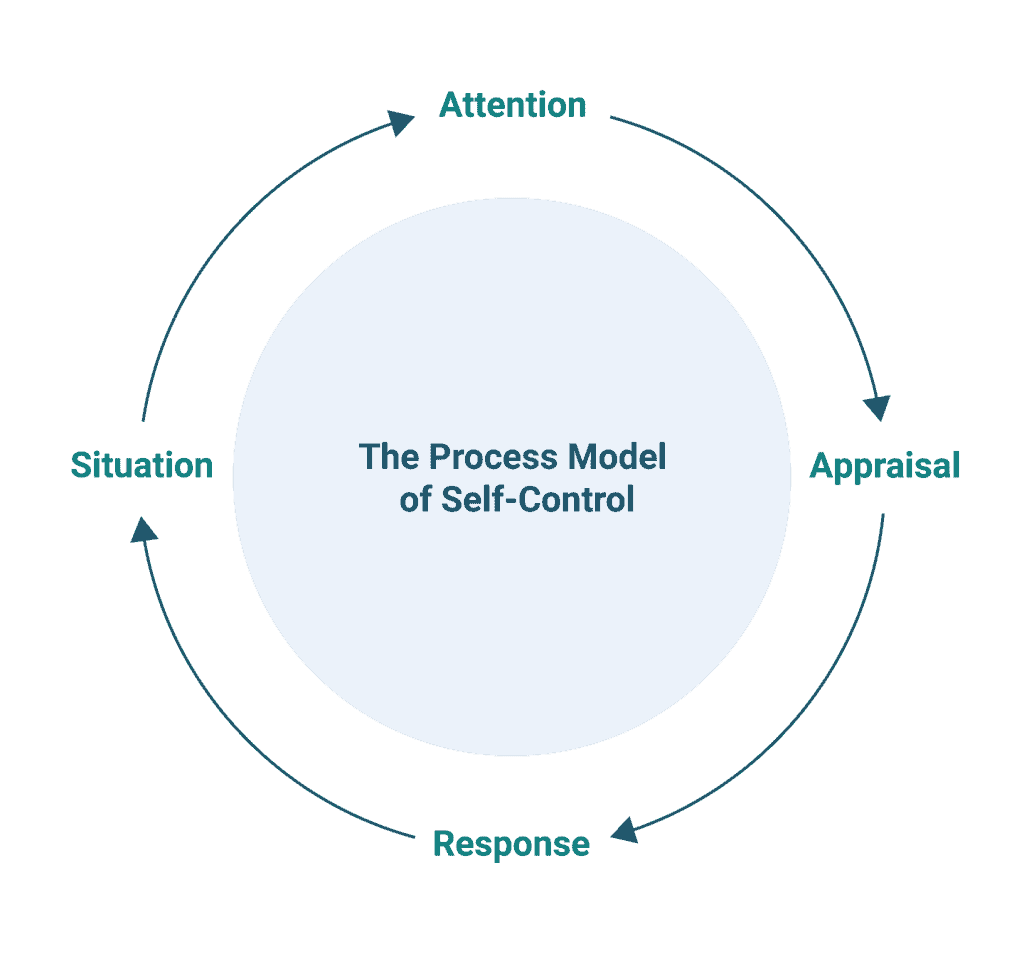

The insight I find so helpful is that every temptation disrupts a goal we have for ourselves. If we are tempted to sit and watch TV when we want to get more exercise—or tempted to play video games when we want to study—or tempted to eat a candy bar when we want to lose 10 pounds—the temptation deflects us from important long-term goals with a short-term reward. Duckworth and co-author James Gross offer a diagram to understand the process of temptation:

Something about our situation offers a temptation that threatens to deflect us from a long-term goal. The video game is available in our room. Then we pay attention to the temptation; we think of playing the video game. We evaluate the temptation, and finally we respond by giving in or resisting. At each point, we can intervene to avoid temptation and make it more likely we’ll make progress toward our long-term goals.

The first point of intervention is to change the situation, which Duckworth and Gross call “situation selection.” A student might, for instance, choose to study at the dining room table, where their parents can see which browser window is open, rather than in their bedroom, where they would have less external monitoring. Or the student could leave a smartphone in the bedroom, to be checked during breaks. In either case, the student selects their own situation, one away from temptation.

“Situation modification” is the choice to change some aspect of the environment, such as logging out of a social media platform while studying, or not keeping candy at home.

“Attention deployment” is an intervention that involves paying attention to what helps you achieve your goal, rather than to what would thwart it. Choosing to look at the teacher rather than at the chat box during class is one example; wearing noise-canceling headphones, to drown out the rest of your family, is another.

“Cognitive change” involves paying attention to the temptation but trying to see it in a different light—for example, looking at a second helping of creamy macaroni and cheese and imagining how you will feel 20 minutes after eating that second helping. A student facing the temptation to put off homework might imagine how they will feel facing the same amount of homework an hour later.

Finally, “response modulation” is simply withstanding the temptation—using will power to avoid giving in.

A key point is that interventions that take place earlier in the cycle are more effective than those that take place later: it is far harder to resist a cookie once it’s in your car than it is to choose a route that avoids driving past your favorite bakery. Similarly, choosing to work in a location away from a video game console is easier than having it in the same room. The closer we are to temptation, the more effort is required of us—and, therefore, the more likely we are to succumb.

Temptations seem to come out of nowhere, and, in the moment, seem to have no cost, which is why it’s helpful for students (and all of us) to remember our long-term goals. The problem with, say, a time-draining social media site is not the site itself, but how it diverts us from the other things we want to spend time on. When the couch and TV are right in front of us, the cost to our long-term goal of getting in shape seems remote. The further away we are from a short-term temptation, the more our longer-term goals can inspire us to make the kind of changes that will help us avoid the temptation altogether. That doesn’t mean throwing out the TV, but it may mean putting an exercise bike in front of it.

The best news is that avoiding temptations can become a habit over time. If you no longer drive past the bakery, you may forget it as a destination. Students who successfully wean themselves off social media during school time might find it less appealing during their free time, and eventually quit.

The moral of the story: the best way to have more will power is to find ways to avoid exercising it.

For a complete listing of MindEdge’s courses about online learning, click here.

Copyright © 2021 MindEdge, Inc.